Permanence and impermanence are a recurring theme in poetry, my favorite two being Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 18′ and William Wordsworth’s ‘A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal’.

Ordinals and the Bitcoin blockchain

Recently, I discovered that it’s now possible to embed text directly into the Bitcoin blockchain using a technology called “Ordinals.”

The technology allows users to inscribe data onto individual satoshi (there’s some debate about the correct plural form: satoshi, satoshis, or even satoshisa, following Japanese grammar). Each inscription can then be shared or traded like an NFT (Non-Fungible Token).

Also see: “The Time Is Out of Joint” – Sanskrit, Shakespeare, Derrida

Storing for eternity?

In 2011, I wrote a series of short “system poems” composed of three to five lines, with words connected both paradigmatically (along the axis of selection) and syntagmatically (along the axis of combination).

The work was inspired by the tradition of structural linguistics, for example, Roman Jakobson’s efforts to link Saussure’s linguistic structures with cognitive operations.

The framework made it possible to generate at least twenty distinct lines from the same basic structure.

At the time, I didn’t think of it as generative art, but I can see the parallels now, even though the term “generative” is usually associated with visual art.

Ownership

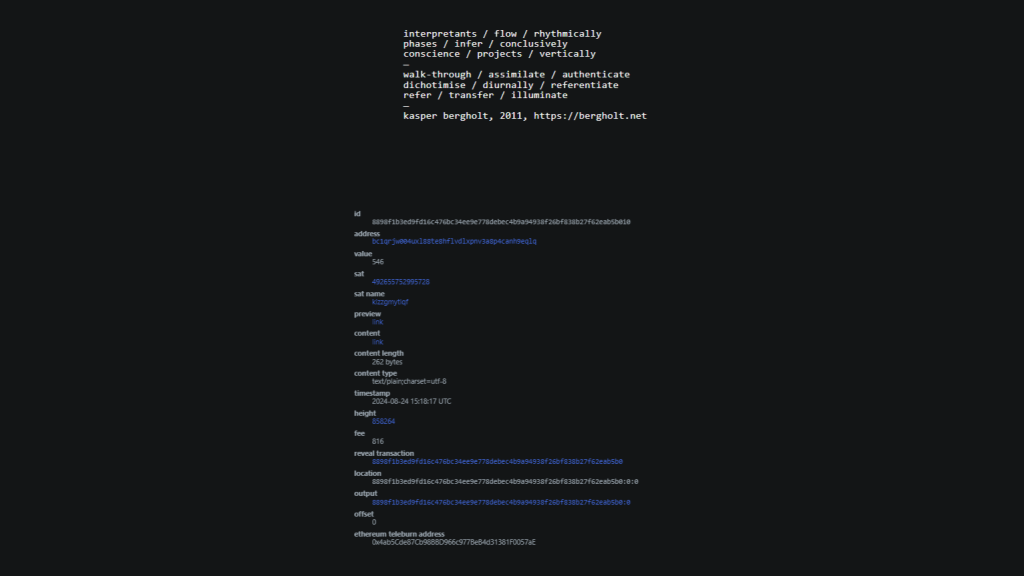

Inscription id: 8898f1b3ed9fd16c476bc34ee9e778debec4b9a94938f26bf838b27f62eab5b0i0

Poem inscribed into the blockchain

The Bitcoin Poem in clear text

interpretants / flow / rhythmically

phases / infer / conclusively

conscience / projects / vertically

—

walk through / assimilate / authenticate

dichotimise / diurnally / referentiate

refer / transfer / illuminate

—

Content of the poem

Thematically, the poem is not about bitcoin, nor was it originally written for the medium of ordinals, as the technology wasn’t available in 2011. The focus is on ensuring a degree of permanence for the poem by burning it into the bitcoin blockchain.

Prior use of the bitcoin blockchain for art projects

Bitcoin Ordinals was used by Chinese artist Yue Minjun for his work, The Human Collection, in May 2024. This collection utilized Ordinals for storing metadata such as titles, descriptions, and mantras.

In his art, Yue Minjun reinterprets significant historical and cultural events, including the moon landing, Woodstock, and Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People.

His collection is considered the first major contemporary art project on the Bitcoin blockchain. As the saying goes, the street finds its own uses for things – a phenomenon now extending into the world of art and technological infrastructure.

Broadly speaking, Yue Minjun is perhaps best known for his 1995 painting Execution, which sold at Sotheby’s London in 2007 for about 2.9$ million, setting a record at the time for a Chinese contemporary artwork.

Etymological glossary

Assimilate – Latin ad- (“to”) + similis (“like”); absorb and integrate.

Authenticate – Greek authentikos (“genuine”); verify as real or true.

Conscience – Latin con- (“with”) + scire (“to know”); moral awareness.

Dichotimise – Greek dichotomia (“cutting in two”); divide into two parts.

Diurnally – Latin diurnalis (“daily”); occurring during the day.

Flow – Old English flōwan; to move smoothly or continuously.

Illuminate – Latin illuminare (“to light up”); to clarify or enlighten.

Infer – Latin in- (“in”) + ferre (“to carry”); derive logically.

Interpretants – Latin interpres (“interpreter”); meaning generated by a sign (Peircean semiotics).

Phases – Greek phasis (“appearance”); stages in a process.

Projects – Latin proicere (“throw forward”); planned work or to extend outward.

Refer – Latin referre (“carry back”); to mention or relate.

Referentiate – From referent + -iate; to treat as a referent (rare usage).

Rhythmically – Greek rhythmos (“measured flow”); in regular beats.

Transfer – Latin trans- (“across”) + ferre (“carry”); move from one to another.

Vertically – Latin vertex (“top, turn”); upward or perpendicular movement.

Walk through – Old English wealcan (“roll”) + þurh (“through”); step-by-step guide.

Analysis of the rhythm of the poem

Here’s a short analysis of the poem’s rhythmical structure in its generative version number 1.

The poem alternates between shorter words (often 1-2 syllables) and longer, polysyllabic words (3-5 syllables), creating a dynamic, varied rhythm.

The shifts in syllable counts between lines give the poem an irregular, syncopated beat.

The alternation between short and long words allows for moments of pause and emphasis (particularly on shorter words like “flow,” “refer,” and “projects”), followed by more extended, flowing words that elongate the rhythm per line.

This creates a sense of push and pull in the rhythm, with sections that feel rapid and clipped followed by more fluid, flowing phrases.

Was the poem written by AI

No, the poem was crafted entirely by hand in 2011.

A Slumber did my Spirit Seal

Vs Sonnet 18 & ‘A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal’

The structure of the bitcoin poem contrasts with standard English metrical lines in iambic pentameter by favoring four-syllable lines in loose structure in contrast to ‘A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal’, mentioned in the introduction, that uses iambic tetrameter (lines with 7 syllables in four iambs) and iambic trimeter (lines with 6 syllables in three iambs) leading to a more regular and flowing rhythm.

Sonnet 18, on the other hand, consists of 14 lines of almost pure iambic pentameter depending on the pronunciation of the words: ‘temperate’, ‘owest’, ‘wanderest’ and ‘growest’.

Glossary: A slumber did my spirit seal

Slumber – Old English slumerian (“doze lightly”), related to sleep; light or gentle sleep.

Did – Old English dyde, past tense of do (dōn); action or performance.

My – Old English mīn; first-person possessive pronoun.

Spirit – Latin spiritus (“breath, soul”), from spirare (“to breathe”); life force or soul.

Seal – Latin sigillum (“small signet”), diminutive of signum (“sign”); to close or fix.

Had – Past tense of have (Old English habban); possession or experience.

No – Old English nā (“not ever”), from ne (“not”) + ā (“ever”); negation.

Human – Latin humanus; of or relating to mankind.

Fears – Old English fǣr (“sudden danger”), later færan (“to frighten”); anxiety, dread.

She – Old English sēo, feminine pronoun; female subject.

Seemed – Old Norse sœma (“to conform”), via Old English sēman (“to conform, fit”); appeared.

A Thing – Old English þing (“assembly, entity”); object or concept.

That Could Not Feel – Feel: Old English fēlan (“to perceive by touch”); to sense.

The Touch – Old French touchier, from Vulgar Latin toccāre; to make physical contact.

Of Earth – Earth: Old English eorþe; ground, soil, world.

Years – Old English gēar; unit of time.

Reel – Old English hreol (“to whirl”), possibly related to spinning; to stagger or rotate.

What are bitcoin ordinals?

A bitcoin ordinal refers to a way of uniquely and inscribing single satoshi (the smallest unit of bitcoin, a bitcoin consists of 100,000,000 satoshi) on the bitcoin blockchain. Ordinals were introduced through a protocol developed by Casey Rodarmor in 2023.

Ordinals enable the tracking and numbering of each single satoshi, making them distinguishable from one another based on the order of mining and movement within the blockchain. Ordinals work entirely within the existing bitcoin structure and do not require any sidechains or separate tokens.

Unlike bitcoin transactions where satoshi are fungible (interchangeable), ordinals allow for a system where individual satoshi can have unique data (known as inscriptions) attached to them.

The inscriptions, such as my bitcoin poem above, can contain images, texts, etc. in form of files, making the blockchain a medium, or infrastructure, for new forms of content creation and distribution, a distributed storage aiming for permanence and immutability.

Also see: Objects for an Ideal Home

Blockchain inscription versus NFTs

t’s important to differentiate. Many NFTs on other blockchains (like Ethereum) do not store the artwork file directly on the main blockchain ledger; instead, they store a token and metadata that points to where the art is stored (often on decentralized storage like IPFS).

The Bitcoin Ordinals protocol is notable because it generally involves inscribing the full content (the art itself) directly into the witness data of a Bitcoin transaction, meaning the art is fully on-chain and stored within the robust security of the Bitcoin blockchain itself.