The oldest, the actual radical word, is ‘es’, Sanskrit ‘asus’, life, the living, that which from out of itself stands and which moves and rests in itself . . . It is noteworthy that ‘is‘ (‘ist’) has maintained itself in all Indo-European languages from the very start (Greek, ‘estin’, Latin, ‘est’, German, ‘ist’)” — Jacques Derrida, The Supplement of the Copula

A declaration of stability (“is”) joined to dislocation (“out of joint”) describing a physical state, a bone wrenched from its socket, painful and dysfunctional.

Applied to time, which encompasses both measurable duration and abstract concepts like eternity, it conveys a world in which the past, the present, and the future no longer align.

“Être juste : au-delà du présent vivant en général – et de son simple envers négatif. Moment spectral, un moment qui n’appartient plus au temps, si l’on entend sous ce nom l’enchaînement des présents modalisés (présent passé, présent actuel : « maintenant », présent futur). Nous questionnons à cet instant, nous nous interrogeons sur cet instant qui n’est pas docile au temps, du moins à ce que nous appelons ainsi. Furtive et intempestive, l’apparition du spectre n’appartient pas à ce temps-là, elle ne donne pas le temps, pas celui-là. « Enter the Ghost, exit the Ghost, re-enter the Ghost » (Hamlet).” — Jacques Derrida, ‘Spectres de Marx’ (‘Exorde’, page 17), Éditions Galilée, 1993.

Disruption in a painful state

The definite article ‘the’ signals a particular context, a specific moment or era that has been disrupted in a painful state, grounded in the physical sensation of dislocation”, which in turn, hinges on the painful feeling of a physical loss of a parent.

Perhaps art can set the bone back in place, to repair, to heal, to set time back into joint?

T.S. Eliot criticizes Hamlet for the play’s lack of object correlatives, but one seems at play here in the externalization, or translation, of inner pain into something physical, alternatively, it reinscribes time as something physical.

It remains unclear whether the line, written in trimeter and anchored in the copula verb ‘is’, in the form of a declarative sentence, should be taken as a novel metaphor that may have unsettled its first audiences, or as an established metaphor already familiar at the time.

I lean toward the latter and would welcome any clarification.

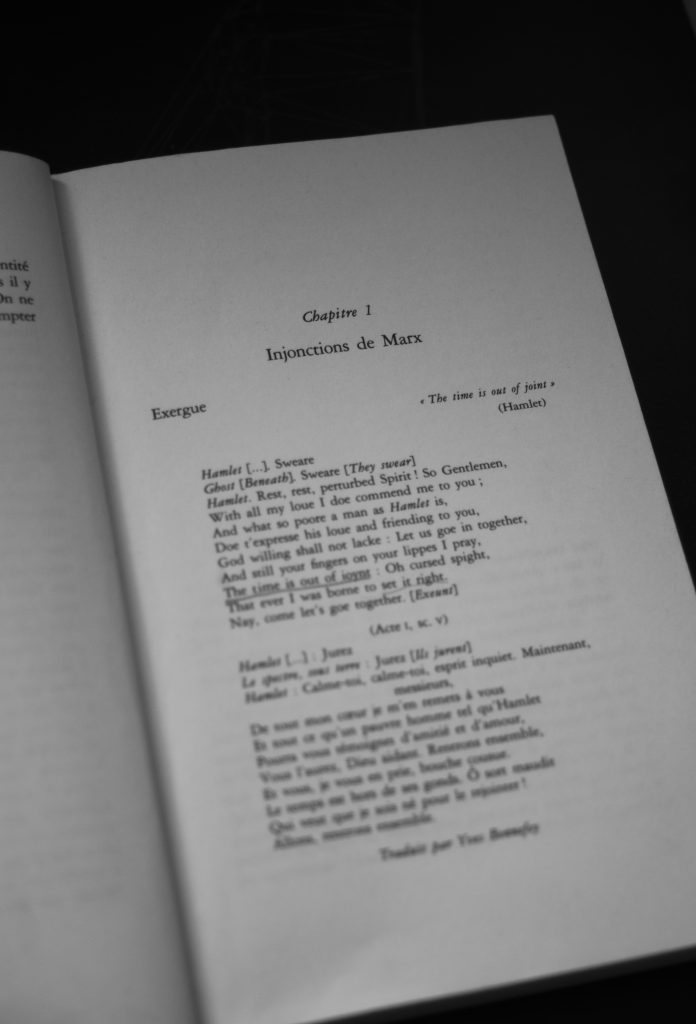

Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5: ‘The Time Is Out of Joint’

Rest, rest, perturbèd spirit.—So, gentlemen,

With all my love I do commend me to you,

And what so poor a man as Hamlet is

May do t’ express his love and friending to you,

God willing, shall not lack. Let us go in together,

And still your fingers on your lips, I pray.

The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite

That ever I was born to set it right!

Nay, come, let’s go together.

— from The Folger Shakespeare edition, ‘The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark’ (1623), act I, towards the end of scene 5.

Derrida on The ‘Time Is Out of Joint’

“In the French translations [of Shakespeare’s Hamlet], the demands are distributed here, it seems, around several major possibilities. These are types. “The Time is out of joint,” time is either ‘le temps’ itself, the temporality of time, or else what temporality makes possible (time as ‘historie’, the way of things are at a certain time, the time that we are living, nowadays, the period), or else, consequently, the ‘monde’, the world as it turns, our world today, our today, currentness itself, current affairs: there were it’s going okay (whither) and there where it’s not going so well, where it is rotting or withering, there where it’s not working [‘ca marche’] or not working well, there where it’s going okay without running as it should nowadays [‘par les temps qui courent‘]. Time: It is ‘le temps’, but also ‘l’histoire, as it is ‘le monde’, time, history, world.”

— Jacques Derrida (1930-2004): Specters of Marx, Routledge, 1994.

Mikhail Bakhtin on Shakespeare

“Semantic phenomena can exist in concealed form, potentially to be revealed only in semantic-cultural contexts of subsequent epochs that are favorable for such disclosure.

The semantic treasures Shakespeare embedded in his works were created and collected through the centuries and even millennia; they lay hidden in the language, and not only in the literary language that before Shakespeare’s time had not entered literature, but also in those strata of the popular language that before Shakespeare’s time had not entered literature, in the diverse genres and forms of speech communication, in the forms of a mighty national culture (primarily carnival forms) that were shaped through millennia, in theater-spectacle genres (mystery plays, farces, and so forth), in plots whose roots go back to prehistoric antiquity, and, finally, in forms of thinking.

Shakespeare, like any artist, constructed his works not out of inanimate elements, not out of bricks, but out of forms that were already heavily laden with meaning, filled with it. We may note in passing that even bricks have a certain spatial form and, consequently, in the hands of the builder they express something.”

— Mikhail Bakhtin, ‘Response to a Question from the Novy Mir Society’, published in Speech Genres & Other Late Essays, 1986.

Epitext / quatrième de couverture

«Un spectre hante l’Europe — le spectre du communisme.»

Spectre fut donc le premier nom, à l’ouverture du Manifeste du parti communiste. Dès qu’on y prête attention, on ne peut plus compter les fantômes, esprits, revenants qui peuplent le texte de Marx. Mais à compter avec eux, pourquoi ne pas interroger aujourd’hui une spectropoétique que Marx aurait laissée envahir son discours ?

Spectres de Marx commence par la critique d’un nouveau dogmatisme, c’est-à-dire une intolérance : « Tout le monde le sait, sachez-le, le marxisme est mort, Marx aussi, n’en doutons plus. » Un « ordre du monde » tente de stabiliser une hégémonie fragile dans l’évidence d’un « acte de décès ». Le discours maniaque qui donne à la clameur jubilaire et obscène que Freud attribue à une phase triomphante dans le travail du deuil. (Refrain de l’incantation : « le cadavre se décompose en lieu sûr, qu’il ne revienne plus, vive le capital, vive le marché, survive le libéralisme économique ! ») Exorcisme et conjuration. Une dénégation tente de neutraliser la nécessité spectrale, mais aussi l’avenir d’un « esprit » du marxisme. Un « esprit » : l’hypothèse de cet essai, c’est qu’il y en a plus d’un. La responsabilité infinie de l’héritier est vouée au discernement, à l’impossible ou non l’autre. Comment ce discernement critique se rapporte-t-il à l’exigence hypercritique — ou plutôt déconstructrice — de la responsabilité ?

Distinguant entre la justice et le droit, croisant les thèmes de l’héritage et du messianisme, Spectres de Marx est surtout le gage — ou le pari intempestif — d’une prise de position : ici, maintenant, demain. Sa portée s’inscrit, en abrégé, à l’angle de quelques inflexions : 1. la conspiration des forces dans une dénégation assourdissante — la « mort de Marx » ; 2. l’espace géo-politique dans lequel résonne cette clameur ; 3. une « graphique » de la spectralité (irréductible à l’ontologie — dialectique de l’absence, de la présence ou de la puissance, — elle se mesure à cette nouvelle donne, et d’abord à ce que la télé-technoscience des « médias » ou la production du « synthétique », du « prothétique » et du « virtuel » transforme plus vite que jamais, dans la structure du vivant ou de l’événement, comme dans la chose publique, l’espace de la représentation politique ou l’État) 4. l’articulation d’une « spectrographie » avec la chaîne d’un discours déconstructif (sur le spectre en général, la différence, la trace, l’itérabilité, etc.) mais aussi avec ce que Marx en esquisse. Et qu’il n’en esquive pas moins : « en même temps », « à la fois ».

‘Fourth cover’ / blurb of French text from ‘Spectrres de Marx’ 1993 edition published in the Effet series edited by Jacques Derrida, Sarah Kofman, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy by Éditions Galilée. The work, Spectres of Marx, consists of material from two lectures given on April 22nd and 23rd 1993 at University of California, Riverside.

The back-cover text is a publisher’s résumé (likely approved by Derrida) that condenses the book’s argument into a compact, almost aphoristic form. It functions as an introduction and invitation, but it is not a passage lifted from the .

Allusions in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock?

It struck me when re-reading the passage from the Folger edition that the two lines:

‘Let us go in together’ and ‘Nay, come, let’s go together’

are echoed (at least to some extent) in T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” intertextually:

‘Let us go then, you and I, When the evening is spread out against the sky’ & ‘Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets’.

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use.

What is a copula verb?

A copular verb is a verb whose primary syntactic function is to serve as a linking element between the grammatical subject and a subject complement (often a predicate nominal or predicate adjective). Derrida’s essay playfully references the dichotomy between the complement, the structurally integral, and the supplement, the structurally peripheral, in the Western tradition.

In contrast to lexical or action verbs, which denote events, processes, or activities, the copula encodes neither action nor dynamic occurrence. Rather it establishes an equative, identificational, or attributive relation between the subject and its predicate.

The essay “Le supplément de copule. La philosophie devant la linguistique” was first published in the journal Langages, issue no. 24 in December 1971, spanning pages 14–39.

Light, Pigments, and the Pharmakon of Art

The fracture of time can be re-read through the prism of light: As the text on Edgar Degas’ Obsession notes, light cannot be owned: it comes to us from stars billions of years distant or from artificial lamps in nanoseconds.

Similarly, art carries traces of both the natural and the artificial, the healing and the toxic, forming an aesthetic and cultural substratum that is later woven into Artificial Intelligence models, where the origins of the individual parts are gradually erased through processes nobody presumably completely understands.

A process that seems to run counter to one of the main principles of the Renaissance, ad fontes (‘to the sources’).

Degas’ pigments, lead white, zinc white, titanium, embody what Derrida calls the pharmakon: at once remedy and poison.

Each layer of paint, revealed by X-ray fluorescence, discloses not a single captured moment but a palimpsest of revisions spanning decades.

What appears immediate, Dancers Practicing in the Foyer, is in fact the accumulation of temporal fractures.

Hamlet’s complaint that “The time is out of joint” is materialized, in a sense, in Degas’ canvas: time embedded as strata, layers that do not align but remain dislocated.

Contemporary literary investigations by Solvej Balle

In Book I of Solvej Balle’s ‘On the Calculation of Volume, the protagonist Tara Shelter, a meticulous observer, journals her experience, cataloging the minutiae of a series of 18th’s of Novembers that form a kind of time loop she’s trapped in: birdsong timings, weather patterns, and conversations.

She initially tries to explain her situation to her husband Thomas, who believes her but resets daily, unaware of prior loops. This creates a distance in their marriage, as Tara moves to a spare bedroom to avoid repeatedly justifying her reality.

The original Danish work is titled Om udregning af rumfang. In Barbare J. Haveland’s English translation, this becomes On the Calculation of Volume. The two titles are rooted in different etymologies.

The Danish rumfang can be broken down into the lexemes rum (“space”) and fang (“to catch”), a compound that requires rephrasing in English, where volume is used instead. This substitution introduces a new semantic layer, since volume derives from the Latin volvere: “to roll up.”

Thus volumina Vergilii refers to Vergil’s “volumes”: his books, scrolls, or body of writings. From this sense, the word developed further in scientific Latin to denote bulk, mass, size, or three-dimensional extent. First a scroll, then a book, and finally volume in its modern meanings.

Quotes from ‘On the Calculation of Volume’, volume I

“No shred of recollection remained. No bath or coffee in the middle of the night, no sleepy talks or nocturnal meals could be dredged up from his memory. There were no twins, no team of horses or lumberjacks. There was a distance between us. There was a hole in time, but there was no way of telling how it had happened. A moment’s inattention and Thomas had lost his eighteenth of November. His memory had been wiped clean again, not by a long night’s slumber, there had been no gradual dissipation. It was as if his eighteenth of November had fallen through a crack in the night, a chasm that had suddenly opened up. But we could not see how it had happened, we could not find the fault in time and we could not come up with an explanation.”

“We were living in two different times, that was a fact. At the start of the day, I was the only one who knew this, that too was a fact. Not until after the morning report, after a short briefing over breakfast and after a comprehensive review of the lists, diagrams and graphs in the living room, did Thomas understand what I was asking him to take part in. It was also a fact that the boundaries were fluid. That there was no specific point at which the shift occurred. We could journey some way into the night together, but sooner or later time fell out of joint.”

“It was a fact hat the objects of the world sometimes stayed with me and sometimes went back to where they had come from. That the way things behaved seemed to be unpredictable. That it helped to keep them physically close, but that there was something unpredictable about the workings of time.”